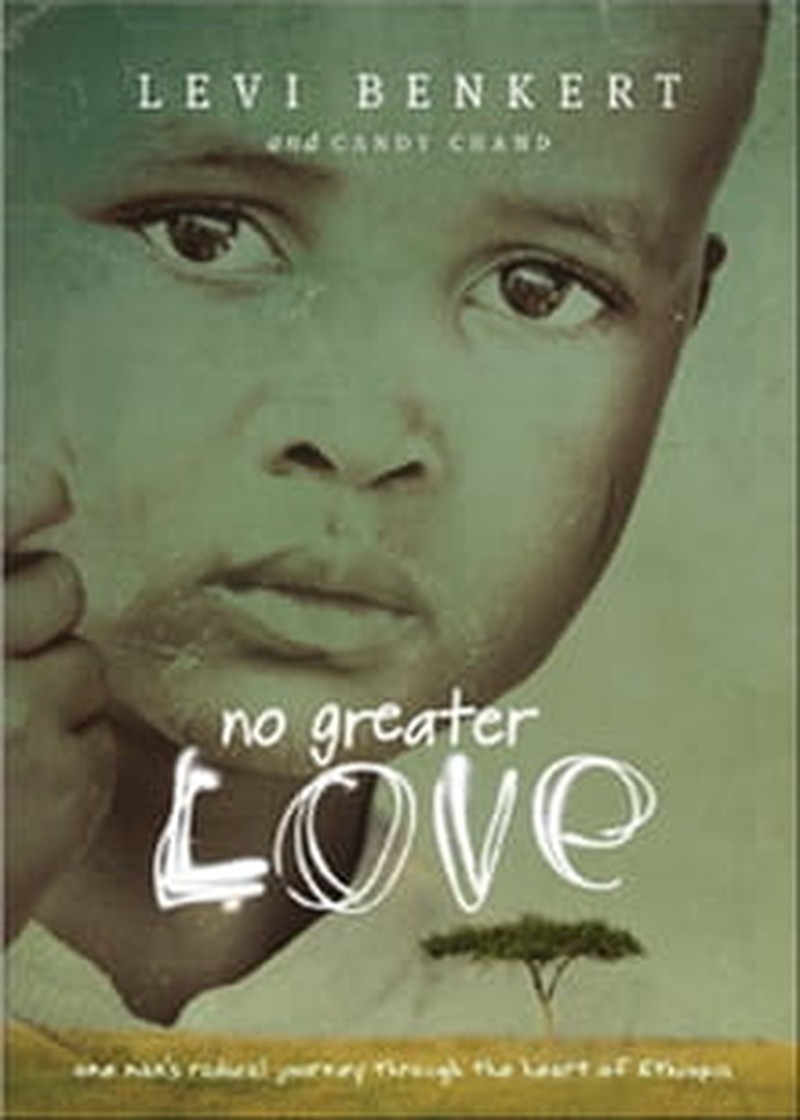

No Greater Love a Stunning Tale of Life, Evil

- Tim Laitinen Crosswalk.com Contributing Writer

- Updated Aug 07, 2012

Author: Levi Benkert and Candy Chand

Title: No Greater Love

Publisher: Tyndale House

No Greater Love is not great literature.

But the story it tells may nevertheless prick your soul. Partly because it’s a true, bizarre story brimming with extremes. And partly because it challenges our assumptions about how we should demonstrate the love of Christ.

In 2009, a young, ambitious California real estate developer named Levi Benkert finds himself trapped in America’s sub-prime mortgage meltdown. Facing imminent bankruptcy, out of the blue, he’s asked by the pastor of a church he’s hardly attended to rescue infants from certain death in Ethiopia.

Some German photographers had stumbled upon a tribe whose parents murder their newborns to pacify evil spirits. But it’s not clear why those Germans didn’t notify international aid agencies instead. It’s also not clear how this church in suburban Sacramento got tasked with the lead rescue role, or why it deems Benkert the best available person to spearhead it.

But apparently, none of that mattered. Kids were being killed and somebody had to do something. So Benkert abruptly abandons his bankrupt company and uproots his wife and three small children to literally the middle of nowhere, without any knowledge of the language or ways of tribal Ethiopia.

Sure enough, in the remote, dusty village of Jinka, the legacy of satanic animism was alive and well, requiring parents to murder their own newborns if cultural etiquette wasn’t followed prior to conception. If a toddler’s top teeth came in before their bottom teeth, parents were to murder that toddler, too. The urgency of the situation is palpable.

Benkert and his wife dive head-first into the challenge before them, and reading their exploits veers between incredulity at their utter naïveté and amazement at their fortitude. Breathlessly fast-paced, Benkert’s narrative churns at the clip of a man who has too much to tell in too little time. Kind of like how he and his wife probably felt as they juggled crushing culture shock and a stunning reality that they were actually saving real human lives. Their altruistic drive apparently overlooks many considerations at which pragmatists would balk.

From California, their church eventually sends other workers to help, but otherwise, this is the Benkert’s baby, so to speak. Along the way, he marvels at how free they feel having sold their possessions in California, and unable to acquire much in their primitive new home. He describes watching his children play contentedly in the Ethiopian dirt with rudimentary toys. When they journey back to the United States, the Benkerts are surprised to find they can barely tolerate the wealth and waste you and I take for granted here.

Not that this is a book about missionaries to Africa bashing American ethnocentricity. But Benkert’s story does question our conventional wisdom regarding how we comfortable Westerners administer overseas outreach.

For example, what is the extent to which our evangelical bureaucracies inhibit urgent responses to distant crises? Especially basic ones like helping widows and orphans? Should we also reconsider the ways we pursue international adoptions? You might be surprised by the solution the Benkerts eventually embrace. Indeed, their first-person encounters with Ethiopia’s adoption industry make this a must-read book for prospective adoptive parents.

If this wasn’t a true story, it could be easy to marginalize Benkert’s tale as an honorable end justifying reckless means. Even Benkert humbly admits that things could have been done better. Yet the fact remains that God used an ordinary middle-class American family to help snatch children from the jaws of death.

Whether this was despite their mistakes or because of their appetite for adventure, how much less of an excuse might the rest of us have when it comes to the ways God may be asking us to serve him?