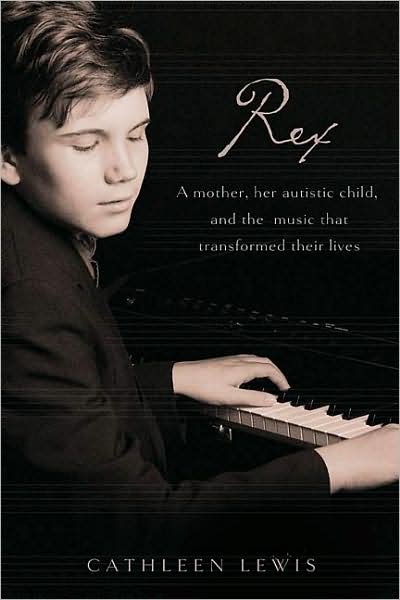

Editor's Note: All parents have dreams for their children - dreams they'll have happy, fulfilling lives. When California native Cathleen Lewis discovered her son Rex was not only blind but also autistic, her dreams for his future received a devastating blow. While Rex's initial difficulties made his future look bleak, glimmers of hope appeared after his second birthday when signs of his unusual gift for music began to emerge. In Rex: A Mother, Her Autistic Child, and the Music that Transformed Their Lives (Thomas Nelson, 2008) Cathleen chronicles her family's journey from despair to faith and unexpected joy. In the interview below, she discusses some of the trials and triumphs of raising an extraordinary child:

Q: Rex was born with a cyst on his brain, which required surgery. Just afterward you discovered that Rex was blind. When he was labeled “autistic” by the age of two, how did you absorb another troubling diagnosis?

Cathleen Lewis: I was in complete denial at first, and angry with his teacher for suggesting it. But, at the same time, I couldn’t deny the obvious. Rex was crawling into a protective shell as the months went by. Classic therapies were not working to rebalance his sensory system. And I asked God why he had allowed this to happen. Rex was a sweet, innocent child—it seemed unthinkable that he would never be able to embrace the sounds and beauty of the world. It would be several more years before I could accept the term “autistic” – I grew into it because it was part and parcel of the child I loved so much. And I was determined to use it as a source of understanding rather than as a label.

Q: We hear a lot about the “autistic spectrum” these days. How severe were Rex’s challenges within the spectrum?

CL: Rex was of course blind, but in addition to that he was extremely sensitive to noise and touch. Putting on his socks was excruciating. Everyday sounds like doors closing, rain falling on the car roof or a ringing telephone were agony for him. Not to mention feeding him. His mouth was so sensitive, he couldn’t eat anything with even the slightest texture, and began drinking most of his meals. Instead of progressively opening up to the world like a typical baby or toddler, he was becoming more and more a prisoner in his own body every day. Only music seemed to have the power to override his sensory reactions.

Q: Statistics reveal that 70% of marriages fail when one of the children has a severe disability. How did your marriage respond to Rex’s challenges?

CL: The typical scenario for a family with a disabled child is that the father earns the living and the mother copes with the rest. Our family was no exception. But this tends to isolate the mother with all the issues and prevents the father from forging the fierce love bond with his child that is necessary to deal with extreme disability. My husband William left before Rex’s second birthday.

Q: So you were suddenly a single mom with a severely disabled child to raise and protect. How did you survive the weight of that responsibility?

CL: Once I was alone, the weight of our lives had become too heavy. I was physically fatigued, emotionally exhausted and often mentally confused. It was if I were standing on the edge of a great precipice, the more I tried to back away, the more the ground crumbled under my feet. Which is when my brother came to visit, and he surprised me by talking about God. Our family had never gone to church, so discussing faith was not the norm for our relationship. I didn’t know if God would have anything to offer Rex or me, but I did know we had nowhere else to turn. We visited a church nearby— with Rex seated in his stroller, I was scared and apologetic that he might disturb the congregation.

Q: What was that first church visit like?

CL: I mentioned to the usher that Rex was blind, and the kindly older man told me, “It’s okay. Don’t worry—we’re used to having kids here.” I don’t know whether it was the kindly words of a stranger, Rex’s look of contentment at the music, or God’s holy presence that caused me to relax in a way I hadn’t done for months. The tears I hadn’t allowed myself before began falling softly, silently, but uncontrollably. Over the next weeks, I began praying for my son and enlisting the church to pray as well. It was days before Rex’s second birthday, and I wanted Rex to talk—through God’s power and for God’s glory.

Q: You mentioned that music seemed to help ease Rex’s sound and touch sensitivities at a young age. How did you discover this?

Q: You mentioned that music seemed to help ease Rex’s sound and touch sensitivities at a young age. How did you discover this?

CL: One day as we drove through rain, with the sound on the roof of our car making Rex scream in pain to the point of near convulsion, I hit a classical station on the radio and watched an instant transformation in him as he heard notes of a Mozart sonata. Then Rex’s father came to visit a short time after his son’s second birthday. With him he brought a 48-key Casio piano keyboard and stand (he had recalled my mention of Rex’s affinity for music). That keyboard transported our son into a friendly world, one he understood, where the pain of his daily existence was held at bay. Over the following months, that little piano hooked Rex into life in a way that nothing else had. It wasn’t just a fluke; it was a passion! He could play that little piano until he dropped from pure exhaustion, and he did just that, day after day.

Q: When did you first realize that Rex’s musical talents were exceptional?

CL: A neighbor, Richard Morton, heard Rex play his little keyboard at a Halloween party in our building. He invited Rex to try out his full-size piano, and Rex amazed us both by playing back hundreds of notes of the Aria of Bach’s Goldberg Variations after hearing it for a first time. Richard had studied music and musical theory in-depth. He explained to me that Rex had perfect pitch, an exceptional memory and could transpose a song instantly from one key to another. Months later, after Richard had been giving Rex piano lessons regularly, he had become so astounded by Rex’s musical feats that he began networking among the musical scientific community to understand the mystery of his musical brain. From that process, he had come up with a label, and told me that Rex was a prodigious musical savant. He had to explain what it meant—a scientific anomaly, causing an extremely rare island of pure genius to exist in a sea of disability. I couldn’t view my child that way, however. All I had ever wanted for him was normalcy!

Q: How did “60 Minutes” learn about Rex? Were you eager to have them meet him?

CL: Richard was first contacted by a producer who had heard about his work with Rex. I was upset with the idea that Richard was treating my child like a science project and discussing him without my permission. For me, Rex was a child! Granted, he seemed to be exceptional in every aspect, from the challenges he faced daily to his amazing music, but he was a beautiful and guileless child who should be treated as such—not a scientific anomaly. I didn’t want to expose my son to the circus I was sure would result from national media attention.

But then a producer from “60 Minutes” surprised me with a call. She was a mother as well as producer, and she earned my trust with her obvious respect for Rex. I agreed to let them film Rex playing the piano during a benefit concert for the Blind Children’s Center. The “60 Minutes” feature, which profiled Rex, his life and his musical talent, turned out beautifully. It captured the vibrancy of Rex’s personality, and earned an Emmy nomination as “Best Report in a Newsmagazine.” Two years later they did a follow-up profile, earning another Emmy nomination, this time as “Best Feature in a Newsmagazine.” A British documentary crew then shot a feature on Rex and another older savant. Life has not been the same since.

Q: How has Rex’s life changed since the television appearances?

Q: How has Rex’s life changed since the television appearances?

CL: The attention focused on Rex has given him a tremendous sense of self-esteem, which has been vital to his continued development as a person and the overcoming of his intense issues. New performance opportunities have resulted, which have allowed Rex to travel and experience things I never would have dreamed. It has all helped his brain to mature to a place where he now craves all the newness his body and mind couldn’t tolerate before. At long last, he has developed the curious mind he never had as a toddler or very young child, trapped as he was in his autistic mind. He reaches out to the world now, as he has come to know it not as a place of fear as before, but as a place of fun and adventure (not to mention, applause for Rex)! Rex has met another musical savant, sixteen years his senior, and this collaboration has given his musical speech new depth. It has also opened new doors to collaboration with his peers in middle school and high school.

Q: How have you changed during these last several years?

CL: For me, I’ve become much more flexible in my way of thinking. I’ve developed patience I never had before, and I’ve come to understand that beauty and perfection come in many forms. I’ve also learned I need to loosen my grip on the steering wheel of our lives—in that trusting God also means trusting Rex and following his lead. I can provide him with opportunities, but I have to lighten my touch and allow him to move forward at his own pace, in his own time. The whole fact is, Rex loves his life, every second, minute, hour, month and year. My son knows that it is a wonderful life! And through my faith and love for a little boy, so do I.

Q: What advice do you offer to parents whose children are newly diagnosed blind or autistic?

CL: I would advise them that whether it’s blindness or autism, it’s a wide open diagnosis, and that while they should get as much information as they can as fast as they can (early intervention is critical for either a blind or autistic child), they should never allow their children to be pigeonholed or limited by what they supposedly will or will not be able to do. There is no preordained outcome for their child’s development, and their own role as parent is critical. I would emphasize the fact that each blind child or child within the autistic spectrum is highly unique, and that it is essential that they get to know the areas of strength in their own child, and use those as a springboard to work from in addressing the issues. Finally, they should never give up pushing their children to overcome their fears and sensitivities through experience. They should never settle on the status quo, but keep pushing a little more all the time, always, of course, with love and praise. It’s amazing what a good dose of self-esteem can do!

Q: How can churches do a better job of welcoming families of disabled children?

CL: I feel that if churches are committed to outreach all over the world, they should have the same commitment within their own community with the disabled. The starting place is just that—outreach. That’s what Malibu Presbyterian Church did with us, and we felt welcome right from the beginning. So I can suggest other churches follow their model. Churches need to take the initiative to communicate with the parents in order to understand the disability in question, and how they can be of help—through prayer or other supports in the church. They could work with parents to ensure children with disabilities are included in Sunday School programs, as well as other church activities. The directors of specific ministries should communicate their desire to make the children feel welcome, along with brainstorming for appropriate adaptations for activities so that the children can be included.

Cathleen Lewis lives in Malibu, California, where she currently divides her time between her work as a Vision Specialist, the demands of her life as a single mom, raising her complex son, and traveling around the world to select speaking/piano playing engagements with her son to share his gift and the miracle and beauty of Rex.

To read an excerpt of Rex, click here.

For more information or to purchase Rex, click here.