Halloween and Reformation Day: The Connection

Various Protestant churches celebrate Reformation Day on October 31st. Though it may seem like a coincidence that the day is the same as Halloween, there is actually an intimate connection between the two holidays.

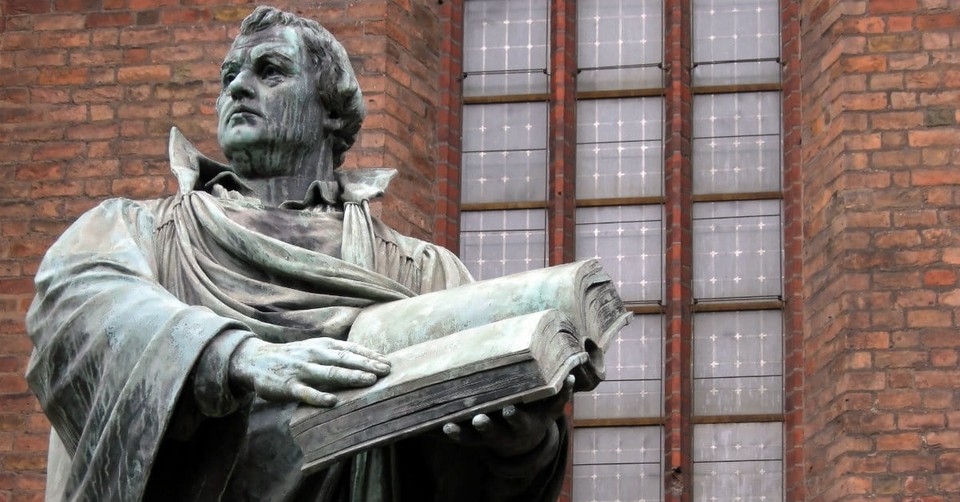

Martin Luther is said to have posted his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of All Saints’ Church (also called Castle Church) on October 31, 1517. This was the eve of All Saints’ Day, or All Hallows’ Day (the origin of the name “Halloween”). It was a time when Christians were particularly focused on their dead. The unfortunate thing was that, by Luther’s time, there was tremendous confusion about just what happened to believers after death – ultimately moving Luther to address the misconceptions associated with the afterlife.

To best understand the Ninety-Five Theses, it is important to explore how Christians had come to view the afterlife by the time of Luther. Early in church history, believers began to celebrate their dead – specifically those who had been martyred for their faith or who were considered outstanding in holiness. Various Christian communities celebrated these “saints”* on different days until the 8th century, when the Western Church chose November 1st to commemorate these heroes of the faith. By 835 AD, November 1st was formally added to the Western Church calendar as All Saints’ Day.

It is not entirely clear when Christians began making a distinction between the souls of the “saints” and the souls of the rest of believers. However, by the 11th century, various congregations were honoring November 2nd as a day to pray for the souls of the dead, believing that while the “saints” immediately entered the presence of God when they died, other believers “pass(ed) out of this world without at once being admitted into the company of the blessed” – in other words, they entered purgatory instead of heaven.1

The concept of purgatory was made official church doctrine at the 1274 Council of Lyons. The council wrote that Christians who had not shown sufficient repentance for their sin needed to be cleansed by purgatorial punishments. Furthermore, the council taught that these punishments could be relieved for oneself (or for those who had died) through “the sacrifices of Masses, prayers, alms, and other duties of piety.”

Though the Roman Catholic Church was careful not to define the nature of purgatory, wild and terrible descriptions developed among Christians. Over the next several centuries, a significant amount of “energy went into understanding purgatory, teaching people about it, and in particular, arranging life in the present in relation to it.”2 The focus of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day was to remember the Christian dead, and it was standard practice for Christians to call on the “saints” or to seek indulgences for help in relieving loved ones (or oneself) from the punishments and terrors of purgatory.

The idea behind an “indulgence” was that the Roman Catholic Church could draw from a “treasury of merit” – a collection of good works done by Christ, Mary, and the “saints” in excess of what was required of them. An indulgence allowed these works to be applied to other Christians to reduce their purgatorial punishment.

Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses were particularly focused on the practice (and corruption) associated with indulgences. Specifically, indulgences were being sold for financial gain, as well as giving people a false assurance of salvation. It is not surprising that Luther posted his theses on October 31st, the eve of All Saints’ and All Souls’ Day, a time which emphasized the distinction between the souls of “saints” and the souls of everyone else, as well as revealed widespread misunderstanding about the power of indulgences (and the afterlife in general).

Since Luther’s work is widely regarded as the catalyst for the Protestant Reformation, October 31st is now celebrated as Reformation Day. It should be noted that, in time, Protestants made sure to articulate a clear teaching about the afterlife to avoid any remaining confusion. The Westminster Confession of Faith, drawn up in 1646, states the following:

“The bodies of men, after death, return to dust, and see corruption: but their souls, which neither die nor sleep, having an immortal subsistence, immediately return to God who gave them: the souls of the righteous, being then made perfect in holiness, are received into the highest heavens, where they behold the face of God, in light and glory, waiting for the full redemption of their bodies. And the souls of the wicked are cast into hell, where they remain in torments and utter darkness, reserved to the judgment of the great day. Beside these two places, for souls separated from their bodies, the Scripture acknowledges none” (Chapter XXXII).

In light of the history of both Halloween and the Reformation, it seems appropriate during this time to remember and rejoice over those who have died in Christ, both heroes of the faith and loved ones – for in biblical terms, all Christians are called “saints” and the blessing of heaven awaits us after death (until God gives us new glorious bodies to live on a new earth).

It comes as no surprise that death is mysterious and terrifying to non-believers (thus the “scary” element of Halloween), but for the Christian, there is no place for fear and superstition regarding the afterlife. Our only “fear” should be awe, wonder, and reverence of the God who “does not treat us as our sins deserve or repay us according to our iniquities. For as high as the heavens are above the earth, so great is his love for those who fear him; as far as the east is from the west, so far has he removed our transgressions from us” (Psalm 103:10-12). This is a message of hope that needs to be shared not only on Halloween and Reformation Day, but in every season of the year!

*The term “saints” is used in quotes when it refers exclusively to heroes of the faith. It should be noted that the New Testament repeatedly uses the word “saints” to refer to ALL believers in Christ.

1. Butler, Alban (edited, revised and supplemented by Herbert Thurston, S.J. and Donald Attwater). Butler’s Lives of the Saints, Vol. 4 (October, November and December) quoting Amalarius of Metz from “Deordine antiphonarii.” P.J. Kenedy and Sons, 1956.

2. Wright, N.T. For All the Saints? Remembering the Christian Departed. Morehouse Publishing, 2003, p. 6.

The content of this article is drawn from a Rose Publishing pamphlet titled Christian Origins of Halloween, © 2012. Used with permission.

Angie Mosteller is founder of Celebrating Holidays, an educational company dedicated to teaching the Christian roots of American holidays. For more information on the history and symbols of Halloween, as well as creative ideas, visit www.celebratingholidays.com.

Publication date: October 24, 2013

Originally published October 24, 2013.