A Family Guide to the Bible

EDITOR’S NOTE: The following is an excerpt from A Family Guide to the Bible by Christin Ditchfield (Crossway).

Chapter One: The History of the Bible: Where Did It Come From?

“And we have the word of the prophets . . . men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit.” - 2 Peter 1:19, 21

The word “Bible” comes from the Greek word biblios, meaning “book.” Christians often refer to this book as “the Word of God,” because we believe that it is literally God’s ord, His message, or as some have said, His love letter to mankind. Every chapter, every verse, ever word of Scripture was inspired by God himself. But how did it come to us? How did we get the book that we hold in our hands today? Did it simply drop down from heaven one day? Was it delivered on somebody’s doorstep by an angelic messenger? The Bible was actually written over a period of more than 1,500 years by as many as forty different authors. God spoke to these men, and they wrote down what He said. He irected them, motivated them, moved them to write—and they responded by picking up their pens. Inspired by the Spirit of God, these men recorded the history of God’s people, His commandments and decrees, prayers and poetry and songs of praise, letters of encouragement and instruction, and prophecies of things to come. At first these words were written on tablets of stone and clay, later on scrolls made of papyrus (plant fiber) and vellum (animal skins).

Over time, as new words—new scrolls—were added, they were gathered together and kept in places of honor in temples and synagogues and churches, to be brought out and read during worship services and special ceremonies. Local congregations of believers treasured them. The scrolls were also carefully copied by hand by scribes and scholars, hen passed on to other communities, countries, and cultures down through the ages. Eventually scholars came up with systems to organize the scrolls, either into categories or chronological order. They divided the Scriptures into sections—chapters and verses and books—that not only made it simpler to find specific passages and study them, but also made it easier to check and cross-check to avoid errors in copying.

By AD 400, many different documents were circulating among the churches, each purporting to be Scripture. The greatest church leaders, religious historians, and Bible scholars of the day came together for a series of church councils. Their goal was to determine which of these writings were truly worthy of being considered sacred Scripture—which were the most respected, the most widely-regarded, the ones that could be verified as authentic, the ones that were consistent with established biblical teaching. They considered the external testimony (what others throughout history had thought of these books) and the internal testimony (what the books said about themselves and each other). And these church leaders prayed. They fervently prayed that God himself would guide them and give them wisdom and discernment.

When all was said and done, the church council had established what is known as the biblical “canon”—a collection of books, each of which had been recognized as meeting a certain standard or specific criterion. These same books make up the Bible we read today.

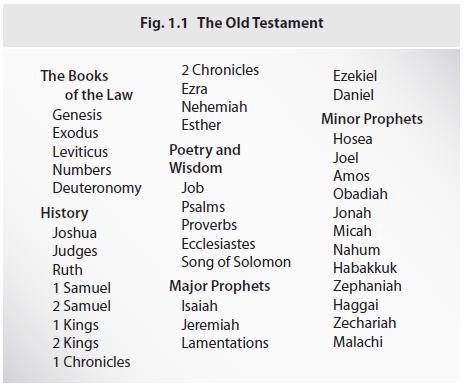

There are sixty-six individual books in the Bible, divided into two sections called “testaments.” The word “testament” means “covenant” or “agreement”—as in a legally binding contract. The Old Testament is God’s covenant or commitment to mankind from the time of creation to the fall of Israel (when it ceased to be an independent nation and its people were sent into exile), approximately 1500 BC to 400 BC. There are thirty-nine books in the Old Testament, written mostly in Hebrew and organized into five different categories: the books of the Law (also known as the Law of Moses or “the Torah”), the Histories, Poetry and Wisdom, Major (longer length) Prophets, and Minor (shorter length) Prophets.

The books of the Old Testament are sometimes referred to as “the Jewish Scriptures” because—along with “rabbinic tradition” (commentary and teachings on the Scriptures by religious leaders)—they are the foundation of the Jewish faith. Devout Jews still study and revere these books and observe these laws today.

Four hundred years after the last book of the Old Testament was written, the New Testament picks up the story with the birth of Jesus, the long-awaited Messiah or “deliverer,” whose coming was foretold by the prophets of old. The New Testament is God’s new covenant or commitment to His people—a fulfillment of promises made in the old covenant. “In the past God spoke to our forefathers through the prophets at many times and in various ways, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son . . .” (Hebrews 1:1–2).

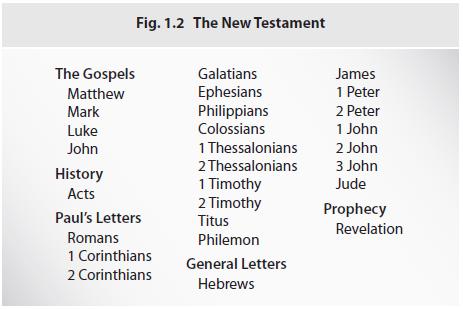

The twenty-seven books of the New Testament were originally written in Greek sometime between AD 48 and AD 95. They are arranged into five categories: the Gospels, History, Paul’s Letters (letters written by the apostle Paul), General Letters (letters written by other apostles or disciples of Jesus), and Prophecy.

Over the years, some Christians have mistakenly come to the conclusion that there is no need to study the Old Testament because it is “old,” and therefore (supposedly) no longer valid. We don’t live under the law of Moses or abide by all the rules and regulations established in Leviticus. We’re not under the terms of the old covenant, but the new. However, Jesus Himself corrected this misunderstanding or misapplication of truth when He said: “Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them. I tell you the truth, until heaven and earth disappear, not the smallest letter, not the least stroke of a pen, will by any means disappear from the Law until everything is accomplished” (Matthew 5:17–18).

As someone once observed:

The New is in the Old concealed; the Old is in the New revealed.

The authors of the New Testament quote the Old Testament literally hundreds and hundreds of times—some scholars have identified as many as two thousand comparable passages! In His preaching and teaching, Jesus quoted from at least twenty-two different books of the Old Testament.

Everything that the Old Testament teaches us about who God is and what He requires of us is absolutely still valid. His ultimate plan and purpose for mankind is still the same. Furthermore, Christianity was born out of Judaism. Knowing our history is key to understanding our present and our future. So both the Old and the New Testament have tremendous value to followers of Jesus today.

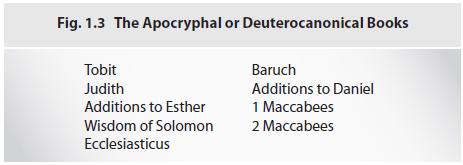

When the church councils first met to establish the biblical canon, there were some writings from both the Old Testament and New Testament era that they chose not to include—books whose authorship couldn’t be verified and whose content couldn’t be authenticated, and books that were not historically regarded as Scripture by either Jewish or Christian religious leaders. Centuries later, the Roman Catholic Church decided to include some of these books in the Catholic Bible. They are referred to by Protestant Christians as the Apocrypha (“Apocrypha” originally meant “secret” or “hidden” writings, and many of these books have a mystical tone.) Roman Catholics call them the “deuterocanonical” or “second canon” books.

During the Middle Ages, the Greek and Hebrew Bible was translated into Latin. Monks living in monasteries devoted their lives to making copies of the Bible the only way they could—by hand! It was painstaking work. It took years to create a single copy of the sacred Scriptures from start to finish. Consequently, copies of the Bible were costly and precious and rare. Only the wealthiest individuals—bishops and kings and queens—could own Bibles of their own. A local church would be glad to have even one copy for the congregation to share. It would be kept on display, and only the priest would know enough Latin to be able to read it.

From the 1300s to the 1500s, a handful of courageous and dedicated Bible scholars began the work of translating the Scriptures into “the language of the common man”—English or German or French, depending on their nationality. These scholars believed that everyone, not just a privileged few, should have access to the powerful, life-changing truths of the Bible for themselves. The translators’ efforts were greatly assisted by Johann Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press, which revolutionized the process of book publishing—no more copying page after page by hand! (The Gutenberg Bible was rinted in 1455.) However, these Bible scholars often found themselves caught up in a political power struggle as corrupt church leaders opposed and outlawed their work. If ordinary people could read the Bible for themselves, they might challenge the authority of the church and question some of its more questionable (and unbiblical) teachings! Many Bible translators were falsely accused of heresy, tortured, and killed for their commitment to the Scriptures, including William Tyndale, “the Father of the English Bible.”

In the 1600s, King James commissioned a committee of fifty-four Bible scholars to create an accurate, authoritative, modern English translation of the Bible. It was first published in 1611, and became known as the King James or “Authorized” Version. For over three hundred years, it was considered the English language Bible.

The twentieth century brought advances in technology, new archaeological discoveries and information, and a renewed interest in Bible translation. Today we have dozens of contemporary English language translations and paraphrases. The Bible has been translated into two thousand other languages, as well.

Sadly, there are still as many as four thousand people groups that don’t have access to the Bible in their own language, and there are still countries and cultures hostile to the Christian faith, in which mere possession of a Bible is a capital offense.

The Reverend Billy Graham once said that perhaps an even greater tragedy is the fact that the Bible remains a “closed book” to millions of people “either because they leave it unread or because they read it without applying its teachings to themselves. . . . The Bible needs to be opened, read and believed.”1

We need to remember what an incredible privilege it is to hold in our hands the Word of God himself, His message, His love letter to us—to be able to read it for ourselves, learn to understand it, and apply it to our own lives today.

Footnotes:

1. Quoted in Henrietta C. Mears, What the Bible Is All About (Ventura, CA: Gospel Light, 1998), 10. 19

A Family Guide to the Bible

Copyright 2009 by Christin Ditchfield

Published by Crossway Books, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers

1300 Crescent Street Wheaton, Illinois 60187

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided for by USA copyright law.

Originally published June 10, 2009.