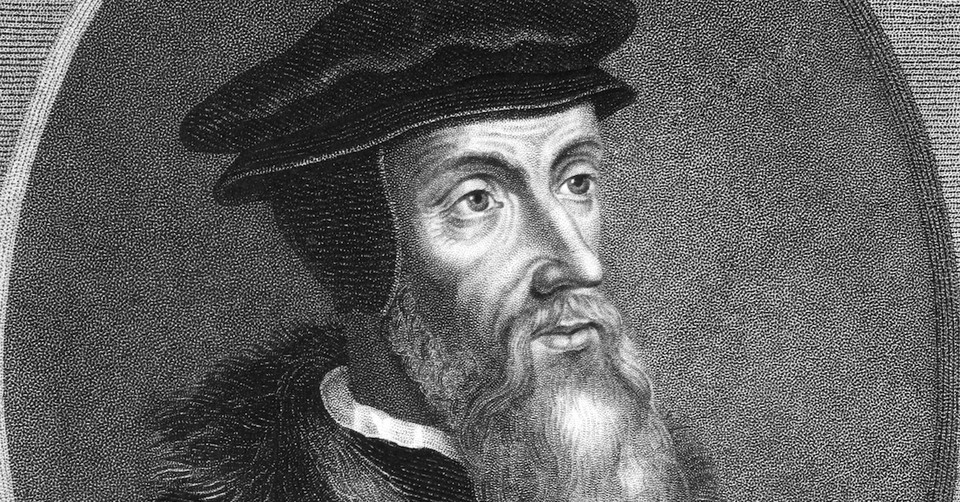

5 Incredible Things John Calvin Did for the Church

John Calvin (1509 – 1564), Reformer, pastor, and prolific writer, was one of the most important theologians that has ever lived. No student of theology can ignore him. For churches who espouse the sovereignty of God in salvation, Calvin’s influence remains central. Whether you love what he believed or despise it, the tenets of his theology continue to reverberate. John Calvin arrived on the fledgling Reformation scene almost from nowhere. A lawyer by training, he was converted in the early 1530s and within a few years became a pastor at St. Peter’s Cathedral church in Geneva. For the next quarter-century (apart from a brief interlude in Strasbourg) he engaged in a prolific ministry of teaching, preaching and reform that turned Europe upside-down. What were some of Calvin's incredible achievements? They are legion. But let us focus on a few of them.

1. Author of The Institutes of the Christian Religion

At the age of 27, Calvin published the first edition of The Institutes of the Christian Religion. At this point, it was a quarter of the size of the final 1559 edition (various expanded editions were published in French and Latin over the course of Calvin’s life). It was a compendium of theology, covering all the major sections of truth in a systematic manner. Calvin had never been to seminary. Having returned to Paris (he studied law at Orleans and Bourges), he came under the influence of Renaissance humanism and its insistence on ad fontes—ensuring that original source material be examined. Newly awakened by the Holy Spirit, Calvin desired to understand the Scriptures, then available in its Latin Vulgate translation, and embarked on a study of Hebrew and Greek so that he could understand what the original source taught. From his study of Scripture emerged Calvin’s summary of what it taught theologically, a compendium of truth providing readers with a map to guide them through the Scriptures, and as the opening sentence makes clear, enable them to know God and know themselves. It is an astonishing achievement that within a few brief years (Calvin was 26 when he wrote the Institutes) he managed to write a book that remains to this day a source of wonder.

The final edition of the Institutes is somewhat difficult to read without knowing the manner in which it came together. Sections of it contain lengthy treatments, while other topics barely get mentioned. The reason lies in the fact that some doctrines were intensely debated during Calvin’s lifetime and others were not. Issues such as the form of church government, the Lord’s Supper, and bondage of the will were matters of intense debate and disagreement and Calvin had much to say about them. Other issues such as baptism, creation, and the Trinity were matters about which there was little disagreement and the Institutes treated them succinctly. Care, therefore, should be exercised not to conclude that the latter topics were not important; they were, but they were not in dispute.

2. John Calvin's Preaching

From the very start of Calvin’s ministry in Geneva, preaching was a priority. And not just preaching but expository preaching! In part, Calvin’s view of preaching is derived from his conviction of Scripture’s inspiration and authority. Preaching is about getting to the truth of what God is saying in the text of Scripture. In part, too, his view of preaching was derived from renaissance convictions about the nature of truth and its relationship to original sources. The meaning of Scripture lay in the grammar and syntax of Greek and Hebrew words. This led him to preach consecutively (verse by verse) through the books of the Bible. Calvin deviated from the medieval quariga (literally, a four-horse chariot) approach to meaning. Origen, for example, insisted that Scripture had four quite distinct meanings: the literal, the moral, the allegorical and the anagogical. The literal is the plain obvious meaning. The moral was what it meant for human behavior. The allegorical meaning is what it means for our faith, beliefs or doctrines. The anagogical meaning is what it tells us about the future (heaven). Calvin rejected this approach.

At his prime, in addition to preaching twice on Sunday, he preached each weekday at noon and the following Wednesday. In the course of two weeks he was committed to preaching ten sermons! He took a few verses at a time and expounded them, giving their sense employing a grammatical-historical hermeneutic. Calvin preached without notes straight from the Hebrew or Greek text, and the city of Geneva viewed Calvin’s preaching as so valuable that in 1548 they employed Denis Ragunier as a stenographer to take down (in French short-hand) every word he said in the pulpit. Over two thousand of Calvin’s sermons exist today. And there are many others that remain in shorthand French awaiting to be read by future generations.

3. John Calvin's Commentaries

In addition to preaching and the Institutes, Calvin gave himself to the publication of lengthy commentaries on individual books of the Bible. In the course of his life, Calvin wrote commentaries on all the books of the New Testament except the book of Revelation and most of the Old Testament. They were published with dedications to European rulers such as Queen Elizabeth. These commentaries continue to be a standard by which modern commentaries are judged. The commentaries are necessary if we are to fully understand Calvin’s theological method. Reading the Institutes, for example, one is often struck by the lack of biblical exegesis and newcomers might draw utterly wrong conclusions. Calvin fully intended readers to make the symbiotic link between the commentaries and the Institutes thereby providing a rich a d comprehensive biblical theology.

4. The Missions of Calvin

We should not fail to notice that Calvin himself was a missionary in Geneva and under his leadership Geneva became a “hub of a vast missionary enterprise” (Frank A. James III, “Calvin and Missions,” Christian History, 5 No. 4 (Fall 1986): 23) and a “dynamic center or nucleus from which the vital missionary energy it generated radiated out into the world beyond” (Philip E. Hughes, The Register of the Company of Pastors of Geneva in the Time of Calvin (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1966), 25). By the mid 1540s, Geneva became the hub from which missionaries travelled to all parts of Europe with the Good News of the gospel. We know, for example, that returning refugees, following a stay in Geneva, were constantly in touch with the company of pastors in Geneva for prayer and advice about how to promote the gospel in their own cities.

As early as 1553, Calvin began sending missionaries to France. In April of 1555 the Register of the Company of Pastors in Geneva for the first time began to officially list men who were sent out from Geneva to “evangelize foreign parts.” Due to the persecution many faced in France, some details were not to be recorded. What we do know is that a network of churches was stablished which included the cities of Aix-en-Provence, Nîmes, Montpellier, Toulouse, Nèrac, Bordeaux, La Rochelle, Nantes, Caen, Dieppe, Tours, and Orlèans. Following persecution by Henry II, a number of the congregations began to form themselves into synods for mutual help and encouragement: half a dozen in and around Poitiers, five or more in Paris, and three in Orlèans. The growth is nothing short of astounding: in 1555 there were five Reformed churches in France. Four years later there were almost 100. Three years after that the number had reached 2,150 with a total membership estimated at 3 million (out of a total population of 20 million). By the time of Calvin’s death in 1564, missionaries had been sent from Geneva all over Europe and as far away as Brazil.

5. Church Polity and Reformation

Upon his return to Geneva in 1541, Calvin wrote his Ecclesiastical Ordinances, a book of church polity that provided for the religious education for the city, especially the children. It was a comprehensive change in the understanding of how the church functioned from that of the medieval Roman Catholic church. He established four groups of church officers: pastors and teachers to preach and explain the Scriptures, elders to rule and pastor the congregation and deacons to attend to administer charity. In addition, Geneva saw the introduction of a Consistory of pastors and elders (Calvin attended every Thursday) to oversee church discipline in both doctrine and practice. Many of the early years were difficulty for Calvin and only in 1555 did his views prevail and he could address himself to other matters. The structure of many conservative churches today reflects Calvin’s reforms of the sixteenth century.

And Much More

There is much more that can be said about Calvin’s astonishing contributions to the church. He was the singular force behind the publication of the Geneva Bible. Many have argued that Calvin’s influence on modern democracy and capitalism is considerable. Furthermore, his singular contributions of distinctive aspects of truth, for example. To name but two: Calvin insisted that Scripture is autopistic—self-authenticating. Since the Bible is God speaking, no higher authority can be found to validate its claims to being divinely inspired. Calvin also added to the doctrine of the Trinity by suggesting that the Jesus is autotheos—God in himself. This was to prevent a tendency in the history of the church to a subordinationism in the understanding of the relationship between the Father and Son.

No finer compliment could have been attributed to John Calvin than the one given him by Philipp Melancthon, who referred to him simply as “the theologian.”

Books

Alistair McGrath, A Life of John Calvin: A Study of Western Culture (Basil Blackwell Ltd., 1990)

Philip E. Hughes, The Register of the Company of Pastors of Geneva in the Time of Calvin (Eerdmans, 1966)

John Piper and David Mathis, With Calvin in the Theater of God: The Glory of Christ and Everyday Life (Crossway, 2010)

Derek W. H. Thomas and John Tweeddale, John Calvin: For a New Reformation (Crossway, 2019)

Bruce Gordon, John Calvin (Yale University Press, 2011)

David W. Hall and Peter A. Lillback, Theological Guide to Calvin’s Institutes: Essays and Analysis (P&R Publishing, 2011)

©GettyImages/GeorgiosArt

Derek Thomas (PhD, University of Wales, Lampeter) is the Chancellor's Professor of Systematic and Practical Theology at Reformed Theological Seminary and senior minister at First Presbyterian Church (ARP) in Columbia, South Carolina. He is the author of many books, including Calvin's Teaching on Job, and serves as a teaching fellow with Ligonier Ministries.

Originally published January 29, 2020.