Slaves, Not Servants: An Interview with John MacArthur

What Does It Mean to Be a Christian?

The early martyrs were crystal clear on what it meant to be a Christian. But ask what it means today and you're likely to get a wide variety of answers, even from those who identify themselves with the label.

For some, being "Christian" is primarily cultural and traditional, a nominal title inherited from a previous generation, the net effect of which involves avoiding certain behaviors and occasionally attending church. For others, being a Christian is largely political, a quest to defend moral values in the public square or perhaps to preserve those values by withdrawing from the public square altogether. Still more define Christianity in terms of a past religious experience, a general belief in Jesus, or a desire to be a good person. Yet all of these fall woefully short of what it truly means to be a Christian from a biblical perspective.

Interestingly, the followers of Jesus Christ were not called "Christians" until ten to fifteen years after the church began. Before that time, they were known simply as disciples, brothers, believers, saints, and followers of the Way (a title derived from Christ's reference to Himself, in John 14:6, as "the way, the truth, and the life" [NKJV]). According to Acts 11:26, it was in Antioch of Syria that "the disciples were first called Christians" and since that time the label has stuck.

The name was initially coined by unbelievers as an attempt to deride those who followed a crucified Christ.6 But what began as a ridicule soon became a badge of honor. To be called "Christians" (in Greek, Christianoi) was to be identified as Jesus' disciples and to be associated with Him as loyal followers. In a similar fashion, those in Caesar's7 household would refer to themselves as Kaisarianoi ("those of Caesar") in order to show their deep allegiance to the Roman Emperor. Unlike the Kaisarianoi, however, the Christians did not give their ultimate allegiance to Rome or any other earthly power; their full dedication and worship were reserved for Jesus Christ alone.

Thus, to be a Christian, in the true sense of the term, is to be a wholehearted follower of Jesus Christ. As the Lord Himself said in John 10:27, "My sheep hear My voice, and I know them, and they follow Me" (emphasis added). The name suggests much more than a superficial association with Christ. Rather, it demands a deep affection for Him, allegiance to Him, and submission to His Word. "You are My friends if you do what I command you," Jesus told His disciples in the Upper Room ( John 15:14). Earlier He told the crowds who flocked to hear Him, "If you continue in My word, then you are truly disciples of Mine" ( John 8:31); and elsewhere: "If anyone wishes to come after Me, he must deny himself, and take up his cross daily and follow Me" (Luke 9:23; cf. John 12:26).

When we call ourselves Christians, we proclaim to the world that everything about us, including our very self-identity, is found in Jesus Christ because we have denied ourselves in order to follow and obey Him. He is both our Savior and our Sovereign, and our lives center on pleasing Him. To claim the title is to say with the apostle Paul, "To live is Christ and to die is gain" (Phil. 1:21).

A Word That Changes Everything

Since its first appearance in Antioch, the term Christian has become the predominant label for those who follow Jesus. It is an appropriate designation because it rightly focuses on the centerpiece of our faith: Jesus Christ. Yet ironically, the word itself appears only three times in the New Testament—twice in the book of Acts and once in 1 Peter 4:16.

In addition to the name Christian, the Bible uses a host of other terms to identify the followers of Jesus. Scripture describes us as aliens and strangers, citizens of heaven, and lights to the world. We are heirs of God and joint heirs with Christ, members of His body, sheep in His flock, ambassadors in His service, and friends around His table. We are called to compete like athletes, to fight like soldiers, to abide like branches in a vine, and even to desire His Word as newborn babies long for milk. All of these descriptions—each in its own unique way— help us understand what it means to be a Christian.

Yet, the Bible uses one metaphor more frequently than any of these. It is a word picture you might not expect, but it is absolutely critical for understanding what it means to follow Jesus. It is the image of a slave.

Time and time again throughout the pages of Scripture, believers are referred to as slaves of God and slaves of Christ.8 In fact, whereas the outside world called them "Christians," the earliest believers repeatedly referred to themselves in the New Testament as the Lord's slaves.8 For them, the two ideas were synonymous. To be a Christian was to be a slave of Christ.9

The story of the martyrs confirms that this is precisely what they meant when they declared to their persecutors, "I am a Christian." A young man named Apphianus, for example, was imprisoned and tortured by the Roman authorities. Throughout his trial, he would only reply that he was the slave of Christ.10 Though he was finally sentenced to death and drowned in the sea, his allegiance to the Lord never wavered.

Other early martyrs responded similarly: "If they consented to amplify their reply, the perplexity of the magistrates was only the more increased, for they seemed to speak insoluble enigmas. ‘I am a slave of Caesar,' they said, ‘but a Christian who has received his liberty from Christ Himself;' or, contrariwise, ‘I am a free man, the slave of Christ;' so that it sometimes happened that it became necessary to send for the proper official (the curator civitatis) to ascertain the truth as to their civil condition."11

But what proved to be confusing to the Roman authorities made perfect sense to the martyrs of the early church.12 Their self-identity had been radically redefined by the gospel. Whether slave or free in this life, they had all been set free from sin; yet having been bought with a price, they had all become slaves of Christ. That is what it meant to be a Christian.13

The New Testament reflects this perspective, commanding believers to submit to Christ completely, and not just as hired servants or spiritual employees—but as those who belong wholly to Him. We are told to obey Him without question and follow Him without complaint.

Jesus Christ is our Master—a fact we acknowledge every time we call Him "Lord." We are His slaves, called to humbly and wholeheartedly obey and honor Him.

We don't hear about that concept much in churches today. In contemporary Christianity the language is anything but slave terminology. 14 It is about success, health, wealth, prosperity, and the pursuit of happiness. We often hear that God loves people unconditionally and wants them to be all they want to be. He wants to fulfill every desire, hope, and dream. Personal ambition, personal fulfillment, personal gratification—these have all become part of the language of evangelical Christianity—and part of what it means to have a "personal relationship with Jesus Christ."

Instead of teaching the New Testament gospel—where sinners are called to submit to Christ—the contemporary message is exactly the opposite: Jesus is here to fulfill all your wishes. Likening Him to a personal assistant or a personal trainer, many churchgoers speak of a personal Savior who is eager to do their bidding and help them in their quest for self-satisfaction or individual accomplishment.

The New Testament understanding of the believer's relationship to Christ could not be more opposite. He is the Master and Owner. We are His possession. He is the King, the Lord, and the Son of God. We are His subjects and His subordinates. In a word, we are His slaves.

Lost in Translation

Scripture's prevailing description of the Christian's relationship to Jesus Christ is the slave/master relationship.15 But do a casual read through your English New Testament and you won't see it.

The reason for this is as simple as it is shocking: the Greek word for slave has been covered up by being mistranslated in almost every English version—going back to both the King James Version and the Geneva Bible that predated it.16 Though the word slave (doulos in Greek) appears 124 times in the original text,17 it is correctly translated only once in the King James.

Most of our modern translations do only slightly better.18 It almost seems like a conspiracy. Instead of translating doulos as "slave," these translations consistently substitute the word servant in its place. Ironically, the Greek language has at least half a dozen words that can mean servant. The word doulos is not one of them.19 Whenever it is used, both in the New Testament and in secular Greek literature, it always and only means slave. According to the Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, a foremost authority on the meaning of Greek terms in Scripture, the word doulos is used exclusively "either to describe the status of a slave or an attitude corresponding to that of a slave."20 The dictionary continues by noting that

the meaning is so unequivocal and self-contained that it is superfluous

to give examples of the individual terms or to trace the history of the

group. . . . [The] emphasis here is always on "serving as a slave." Hence

we have a service which is not a matter of choice for the one who renders

it, which he has to perform whether he likes it or not, because he

is subject as a slave to an alien will, to the will of his owner. [The term

stresses] the slave's dependence on his lord.

While it is true that the duties of slave and servant may overlap to some degree, there is a key distinction between the tw servants are hired; slaves are owned.21 Servants have an element of freedom in choosing whom they work for and what they do. The idea of servanthood maintains some level of self-autonomy and personal rights. Slaves, on the other hand, have no freedom, autonomy, or rights. In the Greco- Roman world, slaves were considered property, to the point that in the eyes of the law they were regarded as things rather than persons.22 To be someone's slave was to be his possession, bound to obey his will without hesitation or argument.23

But why have modern English translations consistently mistranslated doulos when its meaning is unmistakable in Greek? There are at least two answers to this question. First, given the stigmas attached to slavery in Western society, translators have understandably wanted to avoid any association between biblical teaching and the slave trade of the British Empire and the American Colonial era.24 For the average reader today, the word slave does not conjure up images of Greco- Roman society but rather depicts an unjust system of oppression that was finally ended by parliamentary rule in England and by civil war in the United States. In order to avoid both potential confusion and negative imagery, modern translators have replaced slave language with servant language.

Second, from a historical perspective, in late-medieval times it was common to translate doulos with the Latin word servus. Some of the earliest English translations, influenced by the Latin version of the Bible, translated doulos as "servant" because it was a more natural rendering of servus.25 Added to this, the term slave in sixteenth-century England generally depicted someone in physical chains or in prison. Since this is quite different from the Greco-Roman idea of slavery, the translators of early English versions (like the Geneva Bible and the King James) opted for a word they felt better represented Greco- Roman slavery in their culture. That word was servant. These early translations continue to have a significant impact on modern English versions.26

But whatever the rationale behind the change, something significant is lost in translation when doulos is rendered "servant" rather than "slave." The gospel is not simply an invitation to become Christ's associate; it is a mandate to become His slave.

[Editor's note: Taken from Slave: The Hidden Truth about Your Identity in Christ (pages 10-19), by John MacArthur ©2010 Thomas Nelson Publishers. Used by permission.]

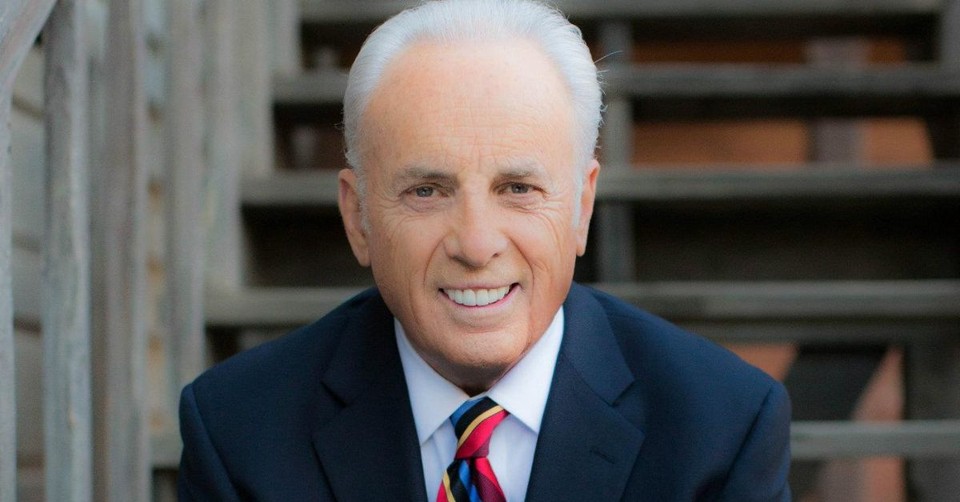

Editor's Note: John MacArthur passed away on July 14, 2025.

Widely known for his thorough, candid approach to teaching God's Word, John MacArthur is a fifth-generation pastor, a popular author and conference speaker, and has served as pastor-teacher of Grace Community Church in Sun Valley, California since 1969. John and his wife, Patricia, have four grown children and fourteen grandchildren.

John's pulpit ministry has been extended around the globe through his media ministry, Grace to You, and its satellite offices in Canada, Europe, India, New Zealand, and Singapore. In addition to producing daily radio programs for nearly 2,000 English and Spanish radio outlets worldwide, Grace to You distributes books, software, audiotapes, and CDs by John MacArthur. In thirty-six years of ministry, Grace to You has distributed more than thirteen million CDs and audiotapes.

Photo Credit: ©Grace to You

NOTES:

6. As the apostle Paul explains in 1 Corinthians 1:23, the idea of a crucified Christ was "to the Jews a stumbling block and to the Greeks foolishness" (nkjv). Those who followed Jesus Christ (having been labeled as Christians) were denounced as heretics by unbelieving Jews and derided as fools by unbelieving Gentiles.

7. The Hebrew word for slave, ‘ebed, can speak of literal slavery to a human master. But it is also used metaphorically to describe believers (more than 250 times), denoting their duty and privilege to obey the heavenly Lord. The New Testament's use of the Greek word, doulos, is similar. It, too, can refer to physical slavery. Yet it is also applied to believers—denoting their relationship to the divine Master—at least 40 times (cf. Murray J. Harris, Slave of Christ [Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1999], 20-24). An additional 30-plus NT passages use the language of doulos to teach truths about the Christian life.

8. See, for example, Romans 1:1; 1 Corinthians 7:22; Galatians 1:10; Ephesians 6:6; Philippians 1:1; Colossians 4:12; Titus 1:1; James 1:1; 1 Peter 2:16; 2 Peter 1:1; Jude 1; and Revelation 1:1.

9. According to the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (hereinafter referred to as ISBE), some commentators have proposed that the term "Christian" literally means "slave of Christ." For example, "Deissmann (Lict vom Osten, 286) suggests that Christian means slave of Christ, as Caesarian means slave of Caesar" ( John Dickie, "Christian," in James Orr, ed., ISBE [Chicag Howard-Severance Company, 1915], I:622).

10. Stringfellow Barr, The Mask of Jove (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1966), 483.

11. Northcote, Epitaphs of the Catacombs, 140.

12. Karl Heinrich Rengstorf, under "δοῦλος," in Gerhard Kittel, ed.; Geoffrey Bromiley, trans., Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, vol. 2, notes that, "In the early Church the formula [slave of God or slave of Christ] took on a new lease of life, being used increasingly by Christians in self-designation (cf. 2 Clem. 20, 1; Herm. m. 5, 2, 1; 6, 2, 4; 8, 10, etc.)" (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964, 274).

13. In a second-century letter from the churches of Lyons and Vienne to the churches of Asia and Phrygia, the anonymous authors began by designating themselves the "slaves of Christ" (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 5.1-4). They continued by describing the widespread persecution they had endured, including the martyrdoms that many in their midst had experienced.

14. As Janet Martin Soskice explains, "Talk of the Christian as ‘slave of Christ' or ‘slave of God' which enjoyed some popularity in the Pauline Epistles and early Church is now scarcely used, despite its biblical warrant, by contemporary Christians, who have little understanding for or sympathy with the institution of slavery and the figures of speech it generates" (The Kindness of God: Metaphor, Gender, and Religious Language [New York: Oxford University Press, 2007], 68).

15. For example, Rengstorf notes the prominence "in the NT [of ] the idea that Christians belong to Jesus as His δοῦλοι [slaves], and that their lives are thus offered to Him as the risen and exalted Lord" (Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, s .v. "δοῦλος" 2:274).

16. Even earlier, John Wycliffe and William Tyndale rendered the Greek doulos with the English word "servant."

17. According to Harris, "this word [doulos] occurs 124 times in the New Testament and its compound form syndoulos (‘fellow-slave') ten times" (Slave of Christ, 183). The verb form also occurs an additional eight times.

18. Two exceptions to this are E. J. Goodspeed's The New Testament: An American Translation (1923) and the Holman Christian Standard Version (2004), both of which consistently render doulos a s "slave."

19. Cf. Harris, Slave of Christ, 183.

20. Rengstorf, Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, s .v. "δοῦλος," 2:261.

21. As Walter S. Wurzburger explains, "To be a slave of God . . . involves more than merely being His servant. Servants retain their independent status. They have only specific duties and limited responsibilities. Slaves, on the other hand, have no rights vis a vis their owners, because they are deemed the property of the latter" (God Is Proof Enough [New York: Devora Publishing, 2000], 37).

22. Speaking of Roman slavery in particular, Yvon Thébert noted that the slave "was equated with his function and was for his master what the ox was for the poor man: an animated object that he owned. The same idea is a constant in Roman law, where the slave is frequently associated with other parts of a patrimony, sold by the same rules that governed a transfer of a parcel of land or included with tools or animals in a bequest. Above all he was an object, a res mobilis. Unlike the waged worker, no distinction was made between his person and his labor" ("The Slave," 138-74 in Andrea Giardina, ed., The Romans [Chicag University of Chicago, 1993], 139).

23. John J. Pilch, under "Slave, Slavery, Bond, Bondage, Oppression," in Donald E. Gowan, ed., Westminster Theological Wordbook of the Bible (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2003), 472, notes that "the Greek noun doulos is a sub-domain of the semantic field ‘control, rule' and describes someone who is completely controlled by something or someone."

24. Ibid., 474. The author points out that "slavery in the ancient world had practically nothing in common with slavery familiar from New World practice and experience of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It would distort the interpretation of the Bible to impose such an understanding on its books."

25. Cf. Harris, Slave of Christ, 184.

26. For an intriguing look at the early English Bible translators' reticence to translate doulos as "slave," see Edwin Yamauchi, "Slaves of God," Bulletin of the Evangelical Theological Society 9/1 (Winter 1966): 31-49. Yamauchi shows that by the late thirteenth century, "slavery disappeared from northwestern Europe. . . . Slavery therefore was known to the 17th-century Englishmen—at least at the beginning of that century—not as an intimate, accepted institution but rather as a remote phenomenon" (p. 41). Their concept of a "servant" was shaped by their knowledge of serfdom—a kind of servitude in which the laborer was bound to the land he worked. Although he was duty-bound to the landowner, his services could only be sold when the land itself was sold. By contrast, "slavery" in their minds evoked "the extreme case of a captive in fetters" (p. 41), an image of cruelty that they understandably wished to avoid. But in so doing they unwittingly diminished the force of the actual biblical expression. In Yamauchi's words, "If we keep in mind what ‘slavery' meant to the ancients, and not what it means to us or the 17th-century theorists, we shall gain a heightened understanding of many passages in the New Testament" (43). See also Harris, Slave of Christ, 184.

This article originally appeared on Christianity.com.

Publication date: April 4, 2011

Originally published April 04, 2011.