What to Do with the Problem of Suffering

Throughout history, virtually every society has sought to teach people how to deal with pain and suffering. Sadly, our current culture has largely neglected this task. Why? Because for generations we’ve embraced a secular worldview that assumes that the material world is all there is, and that, thus, pain has no meaningful part to play in life. And yet we feel the inadequacy of this approach and yearn for an answer beyond it, don’t we? Which is why we as a secular society borrow concepts from religion when tragedy strikes. After every terrorist attack or mass shooting, my Facebook news feed fills up with my atheist and agnostic friends offering “prayers” and “thoughts” to the victims and families of these tragedies. They have to borrow language from religious traditions because their own view of the world offers nothing to them. Several of my friends use the language of karma in normal life (“What goes around comes around,” etc.). But such words don’t make sense in the face of tragedy. Karmic theology, when truly understood, blames the victims for their fate. So people borrow aspects of the Christian worldview when tragedy strikes because “Christianity teaches that, contra fatalism, suffering is overwhelming; contra Buddhism, suffering is real; contra karma, suffering is often unfair; but contra secularism, suffering is meaningful.”

Underlying this entire discussion is another, deeper question. What is “good”? Far beyond the suffering we experience in our individual lives, philosophers point out that suffering may be a necessary reality for the universe to reach its greatest good. They point out that in order to have a maximum joy, the opposite potential must exist as well. While this is not the Christian worldview, there are some affinities. In the Christian worldview, the greatest good is God. God loves, and his love is expressed in acts of creation; when human beings rebel and disrupt the moral justice of the universe, God’s response is ultimately one of love, communicated in an act of redemption and salvation. When God was faced with the question of evil and suffering in the Garden of Eden, he could have changed Adam and Eve into robots. He could have destroyed them. But he would have sacrificed a greater good, that of a loving relationship with humanity. Though we may not understand all of the reasons why, it is possible that God allowed evil and suffering so that the greater good could exist.

In Christian theology, the cross of Christ is the moment where the greatest good, glory, and love of God is revealed to the universe. Why was such suffering necessary? Because human sin had disrupted the moral order, spreading evil. God turns human evil into our redemption and salvation, and so the killing of our Creator is transformed into the supreme act of love. “God preferred on the whole the global result of the drama of sin and salvation to a world without it,” John Stackhouse Jr. writes. Evil “was necessary for that drama and thus evil does have a place in the great scheme of things.” Without it, there would be no such thing as endurance and bravery and sacrifice and courage. In his wisdom God said, “I want the greater good to happen.”

Christianity proclaims a God who is not distant or removed from human suffering. In every other religion, God (or the gods) remains aloof and distant, but the Christian God experienced human existence, identified and empathized with us, suffered with us and for us. And why? Why did God humiliate himself, suffer, and die an awful death? Yes, to save us from our sins, but that is only part of the story. Christianity says that the suffering of the cross is something else: it reveals God’s very nature. Suffering is a reflection of who God is, not just something he did. This is an underappreciated idea within Christianity but a massively important one. The New Testament writers tell us that, yes, our need of saving was the occasion for God’s suffering on the cross, but not its only reason. God suffers, not as something additional to his identity, as just a rescue mission in response to our mistakes, but because of his identity (Colossians 1:15-20; Philippians 2:5-11). In other words, the cross of Christ is not just about soteriology (salvation) but Christology (the identity of God and Jesus himself).

The apostle Paul wrote: “We know that for those who love God all things work together for good” (Romans 8:28). All things, not just some things or good things, but all things. How does that work? I felt a glimpse of it once. My wife was in a car accident when she was eight months pregnant with our first daughter. We thought we had lost the baby for a couple of hours until we got to the hospital and heard a heartbeat. When our daughter was born, I held her in my arms and kissed her with more emotion and intensity because at one point I had faced the possibility of living without her. The pain gave way to a greater glory. I think of this often, and I hold on to hope that when the new creation dawns it will put all the awfulness of the world in context.

In the film version of The Two Towers, Samwise Gamgee tries to convince Frodo to keep pressing on to Mount Doom despite all the pain and suffering they have been through and seen. “It’s like in the great stories, Mr. Frodo,” he says, “the ones that really mattered. Full of darkness and danger they were, and sometimes you didn’t want to know the end because how could the end be happy? How could the world go back to the way it was when so much bad had happened? But in the end it’s only a passing thing, this shadow. Even darkness must pass. A new day will come, and when the sun shines it’ll shine out the clearer.” This is the great hope that Christianity holds out to all of us. That somehow, when we see the greater glory we’ll look back—as crazy as it sounds right now—and we’ll say that on the bell curve of experience, evil and suffering made it all the richer. Perhaps the apostle Paul says it best: “For I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory that is to be revealed to us” (Romans 8:18, emphasis added).

Such is the hope of Christianity.

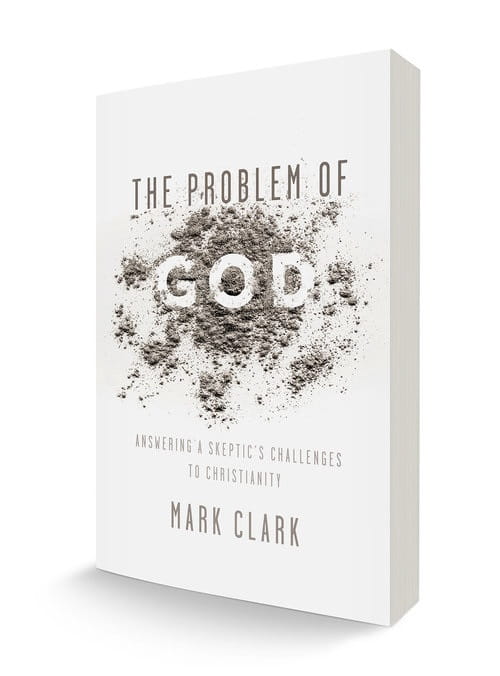

Mark Clark is the founding pastor of Village Church in Vancouver, Canada, one of the fastest growing multi-site churches in North America. Mark combines frank and challenging biblical preaching with real world application and apologetics to speak to both Christians and skeptics alike, confronting questions, doubts, and assumptions about Christianity. His sermons have millions of downloads per year from over 120 different countries.

Image courtesy: ©Thinkstock/DesignPics

Publication date: August 24, 2017

Originally published August 24, 2017.