Trending Articles

Recent News

Impact of America's Negative Net Migration on Ministries This Civilizational Moment Australian Teen Rescues Family Lost at Sea Today’s Athletes Are Bolder than Ever about their Faith in Jesus, Says Benjamin Watson TPUSA Reveals Alternative Halftime Show Lineup, Led by Kid Rock and Country Stars A $2 Million Verdict for Victim of “Gender Affirming Care” Finish MP Faces Trial Over Quoting Bible Verse Today' Show Host Savannah Guthrie's Mother Reported Missing, Police Declare Home a Crime Scene How Christians in Iran Are Responding to Trump's Armada to Iran Jonathan Roumie Steps into Family Comedy with ‘Solo Mio,’ Aiming to Spread ‘Light’ in Film Bills QB Josh Allen Says Fatherhood Matters More Than Football: ‘The Most Important Thing’ The Real Doomsday Clock

Trending Articles

Recent News

Impact of America's Negative Net Migration on Ministries This Civilizational Moment Australian Teen Rescues Family Lost at Sea Today’s Athletes Are Bolder than Ever about their Faith in Jesus, Says Benjamin Watson TPUSA Reveals Alternative Halftime Show Lineup, Led by Kid Rock and Country Stars A $2 Million Verdict for Victim of “Gender Affirming Care” Finish MP Faces Trial Over Quoting Bible Verse Today' Show Host Savannah Guthrie's Mother Reported Missing, Police Declare Home a Crime Scene

Positive Stories

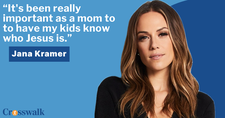

Celebrity

Video

Opinion

Church

Entertainment

Sports

Rams’ Matthew Stafford Goes Viral for 2:30 a.m. Kiss with Sleeping Daughters after Loss

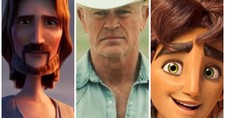

Michael FoustMovies

Politics

Israel

Christian News Headlines - Breaking and Trending Religion News

Crosswalk Headlines - Christian news brought to you by a group of Christian writers and editors who are dedicated to creating a well-rounded look at what’s happening across the globe from a Christian worldview. Our vision is to inform and inspire productive discussion about the current events and online trends that shape our lives, our churches and our world.Crosswalk Headlines includes blog posts about current events and Christian media, breaking news, feature articles, and guest commentaries, many written by respected Christian thinkers.