4 Reasons Parents Feel Sidelined by the Government Regarding the Upbringing of Their Children

Americans Favor Chaplains in Schools but Split on Vouchers and Vaccine Exemptions

Producers of ‘House of David’ Set to Launch Bible-Based Streaming Service on Prime Video

ICE Arrests Iranian Christians at Los Angeles Church

Trending Articles

Candace Cameron Bure’s New Devotional Points Hurting Women to Christ-Centered Hope

Milton QuintanillaRecent News

Trending Articles

Candace Cameron Bure’s New Devotional Points Hurting Women to Christ-Centered Hope

Milton QuintanillaRecent News

Positive Stories

Celebrity

Candace Cameron Bure’s New Devotional Points Hurting Women to Christ-Centered Hope

Milton QuintanillaVideo

Opinion

Church

Entertainment

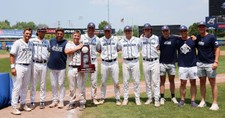

Sports

Movies

Politics

Israel

Christian News Headlines - Breaking and Trending Religion News

Crosswalk Headlines - Christian news brought to you by a group of Christian writers and editors who are dedicated to creating a well-rounded look at what’s happening across the globe from a Christian worldview. Our vision is to inform and inspire productive discussion about the current events and online trends that shape our lives, our churches and our world.Crosswalk Headlines includes blog posts about current events and Christian media, breaking news, feature articles, and guest commentaries, many written by respected Christian thinkers.